Titanoboa thirteen metres, one tonne, The biggest snake ever.

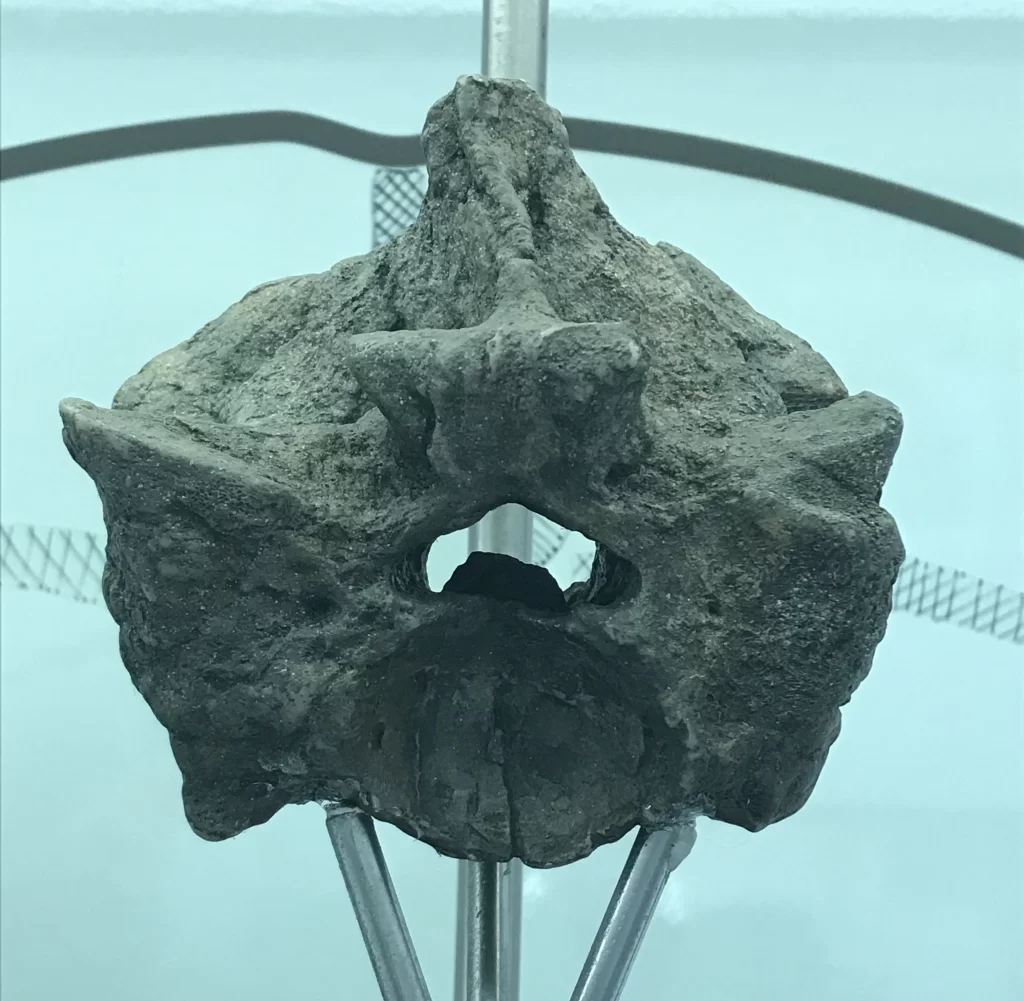

The smaller sized model on the left belongs to the anaconda, a giant snake that can expand to 7 metres in length and weigh as long as 45kg. It’s arguably the biggest snake alive, so just think about how big the owner of the fossilised vertebra on the right would certainly have been! There’s a great reason this brand-new discovery– the biggest snake that ever slithered– has been named Titanoboa.

Titanoboa cerrejonesis is brand-new to science and was found by a group of North American scientists led by Jason Head at the University of Toronto. It’s the latest fossil to emerge from Colombia’s, one of the world’s largest open-pit mines and an unexpected bonanza of ancient reptile fossils.

The giant serpent is carefully related to today’s boas and anacondas, snakes that eliminate their prey with suffocating coils. Living boas come in various sizes, but their similar percentages provided Head the data he required to exercise how big Titanoboa actually was. The foundations of boas are similar enough that, with help from a computer system, you can tell where any type of individual vertebra sits down the length of the snake by looking at its shape. And you can take an accurate stab at the size of the whole snake based upon the size of each vertebra– all participants have the same number of sections, and their size is proportional to the pet’s size.

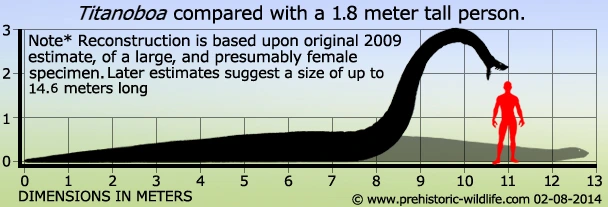

Titanoboa’s fossilised vertebra revealed that it was a whopping 13 metres (42 feet) long. By comparison, the biggest verifiable record for a living snake belongs to a 10-metre-long reticulated python, and that was most likely a striking exception. Large populace surveys of reticulated pythons have actually failed to find individuals longer than 6 metres. By contrast, Head’s team analysed vertebrae from eight different specimens of Titanoboa and located that all of them were roughly the exact same size. A length of 13 metres was fairly regular for this remarkable snake. Not quite Jormungandr, but incredible nonetheless.

Even fossil snakes struggle to match Titanoboa’s dimensions. Five years back, Head’s group used the same methods to put measurements on the previous document holder, Gigantophis. Their study provided it a optimum size of 10.7 metres, easily eclipsed by their newest discovery.

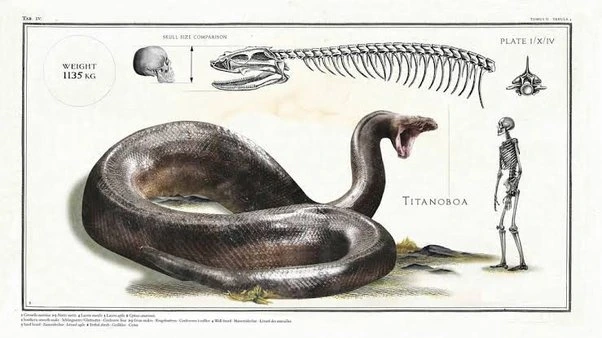

Titanoboa was likewise a hefty animal. Using the length-weight ratios of a rock python and an anaconda as a guide, Head approximated that Titanoboa weighed in at over 1.3 lots. That’s almost thirty times as hefty as the anaconda, the bulkiest species alive today. Its superlative measurements suggest that Titanoboa was not just the biggest snake in background, but likewise the biggest land-living vertebrate following the death of the dinosaurs.

It lived some 58-60 million years ago, when the Cerrejon basin was a huge floodplain, criss-crossed by rivers and nestled within a large tropical jungle. This is exactly the type of habitat that anacondas grow in today, and it’s likely that Titanoboa shared a similar lifestyle. It may well have been aquatic and hunted similar prey, like crocodiles. Certainly, various other fossils from the Cerrejon pit include very early relatives of fishes, turtles and crocodiles– all suitable victim for Titanoboa.

The huge snake’s dimensions even inform us something concerning the environment of this ancient world. Snakes are cold-blooded. Their body temperature level, and therefore their metabolism, depends on their environments, which puts an upper limit onto the evolution of titans. At any type of given temperature level, a snake can only come to be so large before its metabolic rate comes to be too reduced to support its bulk. If Titanoboa was larger than living types, its environment should have been much hotter.

Head estimated that the tropical jungles where it lived should have had typical yearly temperature of 32-33 degrees Celsius, much hotter than the equivalent temperatures for modern exotic forests. These estimates recommend that the forests of that duration were experiencing greenhouse conditions. These problems, part of the planet’s background, have actually been written in rock, left for us to glean amongst the petrified bones of an ancient snake.